По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

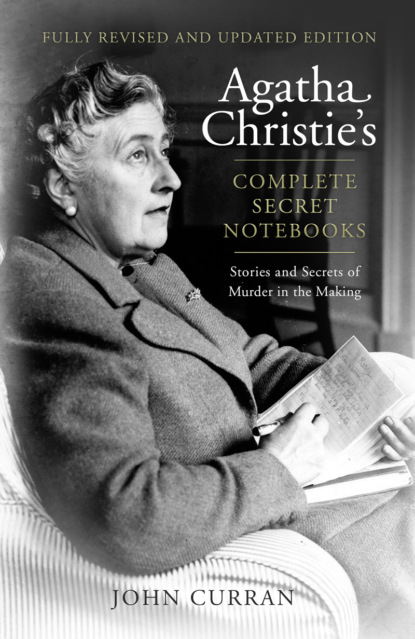

Agatha Christie’s Complete Secret Notebooks

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The list does not contain any great surprises and most fans would probably also select most of the same titles, perhaps replacing The Thirteen Problems and The Moving Finger with The Labours of Hercules and The ABC Murders respectively. Despite, or perhaps because of, Christie’s lifelong association with Hercule Poirot, there are only two of his cases included, while Miss Marple is represented by three. Each decade of her writing career is represented and no less than five of the list are non-series titles.

A further insight, this time into some of her favourite short stories, came two years later. In March 1974 negotiations began between Collins and the author on the thorny subject of that year’s ‘Christie for Christmas’. ‘Thorny’ because the previous year’s Postern of Fate had been a disappointment and, at the request of Christie’s daughter Rosalind, the publisher was not pressing for a new book. The compromise was to be a collection of previously published short stories. Sir William (‘Billy’) Collins mooted the idea of a collection of Poirot short stories but, in a letter (‘Dear Billy’), his creator felt that a book of stories entirely devoted to Hercule Poirot would be ‘terribly monotonous’ and ‘no fun at all’. She hoped to persuade him that the collection ‘could also include what you might describe as Agatha Christie’s own favourites among her own early stories’. To this end she sent him a list described as ‘my own favourite stories written soon after The Mysterious Affair at Styles, some before that’.

Before looking at this list it is important to remember that Dame Agatha was now in her eighty-fourth year, in failing health and a pale shadow of the creative genius of earlier years. She had not written a pure whodunit since A Caribbean Mystery in 1964 and the novels of recent years were all journeys into the past (both her own and her characters’), lacking the ingenious plots and coherent writing of her prime. If she had compiled a similar list even ten years earlier is it entirely possible that it would have been significantly different. Even the description of ‘early stories’ was, as we shall see, misleading.

Christie’s 1974 list reads as follows:

The Red Signal

The Lamp

The Gipsy

The Mystery of the Blue Jar

The Case of Sir Andrew Carmichael

The Call of Wings

The Last Séance

S.O.S.

In a Glass Darkly

The Dressmaker’s Doll

Sanctuary

Swan Song

The Love Detectives

Death by Drowning

Also included are two full-length novels, Dumb Witness and Death Comes as the End, although she acknowledges that the former is too long for inclusion. Perhaps significantly, in both these titles, like her recent publications, there are strong elements of ‘murder in retrospect’; Death Comes as the End deals with murder in ancient Egypt and Dumb Witness finds Poirot investigating a death that occurred some months before the book begins. On her list the titles are numbered but there is no indication that the order is significant. I have regrouped them for ease of discussion.

The first eight titles are all from the 1933 UK-only collection The Hound of Death. As Christie suspected, many of them had been published prior to this in various magazines, the earliest (so far traced) as far back as June 1924 when ‘The Red Signal’ appeared in The Grand. The supernatural is the common theme linking these stories, with only ‘The Mystery of the Blue Jar’, published in The Grand the following month, offering a rational explanation. This type of story was on Christie’s mind as, later in the accompanying letter, she explains that she was planning a ‘semi-ghost story’, adding poignantly, ‘when I am really quite myself again.’ Some of these titles are particularly effective – ‘The Lamp’ has a chilling last line and ‘The Red Signal’, despite its supernatural overtones, shows Christie at her tricky best. ‘The Last Séance’ (March 1927) is a very dark and, unusually for Christie, gruesome story, which also exists in a full-length play version among her papers; while ‘The Call of Wings’ is one of the earliest stories she wrote, described in An Autobiography as ‘not bad’.

Of the remaining six titles, ‘In a Glass Darkly’ (December 1934) and ‘The Dressmaker’s Doll’ (December 1958) are also concerned with supernatural events. The former is a very short story involving precognition while the latter is a late story that Christie felt that she ‘had to write’ while plotting Ordeal by Innocence. She passed it to her agent in mid-December 1957 and it was published the following year; in a note she describes it as a ‘very favourite’ story. ‘Sanctuary’ is also a late story, written in January 1954 and published in October of that year, and features a dying man found on the chancel steps while the sun pours in through the stained-glass window, this picture carrying echoes of similar scenes in the Mr Quin stories. Its setting is Chipping Cleghorn, featured four years earlier in A Murder is Announced, and that novel’s Rev. Harmon and his delightful wife, Bunch, are the main protagonists alongside Miss Marple.

‘Swan Song’, published in The Grand in September 1926, is a surprising inclusion and appears probably due to Christie’s lifelong love of music; despite its country house setting of an opera production, it is a lacklustre revenge story with neither a whodunit nor supernatural element. ‘The Love Detectives’, published in December of the same year, foreshadows the plot of The Murder at the Vicarage and features Mr Satterthwaite, usually the partner of Mr Quin but here making a solo appearance.

The final story, ‘Death by Drowning’, is the last of The Thirteen Problems, although its inclusion jars with the rest of the stories in that collection. Unlike the first twelve problems, ‘Death by Drowning’ (November 1931) does not follow the pattern of a group of armchair detectives solving a crime that has hitherto baffled the police. Miss Marple solves this case without her fellow-detectives and makes one of her very rare forays into working-class territory in a story involving a woman who keeps lodgers and takes in laundry. As an untypical Miss Marple story, it is another unpredictable inclusion.

Overall, the list is, like much of her fiction, very unexpected. Though the absence of Poirot can be explained by the fact that this list is an effort to persuade Collins to experiment with characters other than the little Belgian, there is, for instance, only one Mr Quin story, although she describes them in An Autobiography as ‘her favourite’; and there are only two cases for Miss Marple, neither of which shows her at her best. Why, moreover, no ‘Accident’, no ‘The Witness for the Prosecution’, no ‘Philomel Cottage’? And only three (‘Sanctuary’, ‘The Love Detectives’, ‘Death by Drowning’) can be described as Christie whodunits, albeit not very typical examples. The over-reliance on the supernatural is surprising, although this had been a feature of Christie’s fiction from her early days – The Mysterious Mr Quin, The Hound of Death – and is a plot feature, although usually in the red herring category, of such novels as The Sittaford Mystery, Peril at End House, Dumb Witness, The Pale Horse and Sleeping Murder.

In the event, the proposed book never came to fruition and, despite Christie’s reservations, Poirot’s Early Cases was published in November 1974.

Pre-dating both these lists, An Autobiography names yet another selection of ‘favourites’. Here she describes Crooked House and Ordeal by Innocence as ‘the two [books] that satisfy me best’, and goes on to state that ‘on re-reading them the other day, I find that another one I am really pleased with is The Moving Finger’. A Sunday Times interview with literary critic Francis Wyndham in February 1966 confirms these three titles as favourites, although the interview may have been contemporaneous with the completion of An Autobiography in October 1965 where the mention of the three titles comes in the closing pages. In the specially written Introduction to the Penguin paperback edition of Crooked House she wrote: ‘This book is one of my own special favourites. I saved it up for years, thinking about, working it out, saying to myself “One day when I’ve plenty of time, and really want to enjoy myself – I’ll begin it.”’

Whatever her favourites, there seems little doubt about her least favourite title. Not only was The Mystery of the Blue Train difficult to compose but in An Autobiography she writes ‘Each time I read it again, I think it commonplace, full of clichés, with an uninteresting plot.’ In the Japanese fan letter she calls it ‘conventionally written … [it] does not seem to me to be a very original plot.’ She is even more disparaging in the Wyndham interview when she says, ‘Easily the worst book I ever wrote was The Mystery of the Blue Train. I hate it.’

In view of the inclusion of ‘The Red Signal’ on the 1974 list above, it is appropriate to include ‘The Man Who Knew’, a very short short story – less than 2,000 words – from the Christie Archive, and to compare and contrast it with its later incarnation, ‘The Red Signal’.

The typescript is undated, the only guide a reference in the first paragraph to No Man’s Land, suggesting that the First World War is over. In all probability, its composition pre-dates the publication of The Mysterious Affair at Styles; and this makes its very existence surprising. Very few short story manuscripts or typescripts, even from later in Christie’s career, have survived, so one from the very start of her writing life is remarkable.

The only handwritten amendments are insignificant ones (‘minute service flat’ is changed to ‘little service flat’), but some minor errors of spelling and punctuation have here been corrected.

THE MAN WHO KNEW

Something was wrong …

Derek Lawson, halting on the threshold of his flat, peering into the darkness, knew it instinctively. In France, amongst the perils of No Man’s Land, he had learned to trust this strange sense that warned him of danger. There was danger now – close to him …

Rallying, he told himself the thing was impossible. Withdrawing his latchkey from the door, he switched on the electric light. The hall of the flat, prosaic and commonplace, confronted him. Nothing. What should there be? And still, he knew, insistently and undeniably, that something was wrong …

Methodically and systematically, he searched the flat. It was just possible that some intruder was concealed there. Yet all the time he knew that the matter was graver than a mere attempted burglary. The menace was to him, not to his property. At last he desisted, convinced that he was alone in the flat.

‘Nerves,’ he said aloud. ‘That’s what it is. Nerves!’

By sheer force of will, he strove to drive the obsession of imminent peril from him. And then his eyes fell on the theatre programme that he still held, carelessly clasped in his hand. On the margin of it were three words, scrawled in pencil.

‘Don’t go home.’

For a moment, he was lost in astonishment – as though the writing partook of the supernatural. Then he pulled himself together. His instinct had been right – there was something. Again he searched the little service flat, but this time his eyes, alert and observant, sought carefully some detail, some faint deviation from the normal, which should give him the clue to the affair. And at last he found it. One of the bureau drawers was not shut to, something hanging out prevented it closing, and he remembered, with perfect clearness, closing the drawer himself earlier in the evening. There had been nothing hanging out then.

His lips setting in a determined line, he pulled the drawer open. Underneath the ties and handkerchiefs, he felt the outline of something hard – something that had not been there previously. With amazement on his countenance, he drew out – a revolver!

He examined it attentively, but beyond the fact that it was of somewhat unusual calibre, and that a shot had lately been fired from it, it told him nothing.

He sat down on the bed, the revolver in his hand. Once again he studied the pencilled words on the programme. Who had been at the theatre party? Cyril Dalton, Noel Western and his wife, Agnes Haverfield and young Frensham. Which of them had written that message? Which of them knew – knew what? His speculations were brought up with a jerk. He was as far as ever from understanding the meaning of that revolver in his drawer. Was it, perhaps, some practical joke? But instantly his inner self negatived that, and the conviction that he was in danger, in grave immediate peril, heightened. A voice within him seemed to be crying out, insistently and urgently: ‘Unless you understand, you are lost.’

And then, in the street below, he heard a newsboy calling. Acting on impulse, he slipped the revolver into his pocket, and, banging the door of the flat behind him, hurriedly descended the stairs. Outside the block of buildings, he came face to face with the newsvendor.

‘’Orrible murder of a well known physician. ’Orrible murder of a – paper, sir?’

He shoved a coin into the boy’s hand, and seized the flimsy sheet. In staring headlines he found what he wanted.

HARLEY STREET SPECIALIST MURDERED.

SIR JAMES LAWSON FOUND SHOT THROUGH

THE HEART.

His uncle: Shot!

He read on. The bullet had been fired from a revolver, but the weapon had not been found, thus disposing of the idea of suicide.